Into the Wilds of the Yorkshire Wolds

Time travelling through England's most northerly chalk grasslands and eccentrically named villages

‘East Yorkshire, to the uninitiated, just looks like a lot of little hills. But it does have these marvellous valleys that are caused by glaciers, not rivers. So it’s unusual.’ – David Hockney.

Hockney’s luminous Yorkshire Wolds oil and watercolour landscapes are a far cry from his iconic swimming pool paintings from sixties and seventies LA, but they are every bit as characteristic of their location and showcase his love of the changing seasons in the county of his birth.

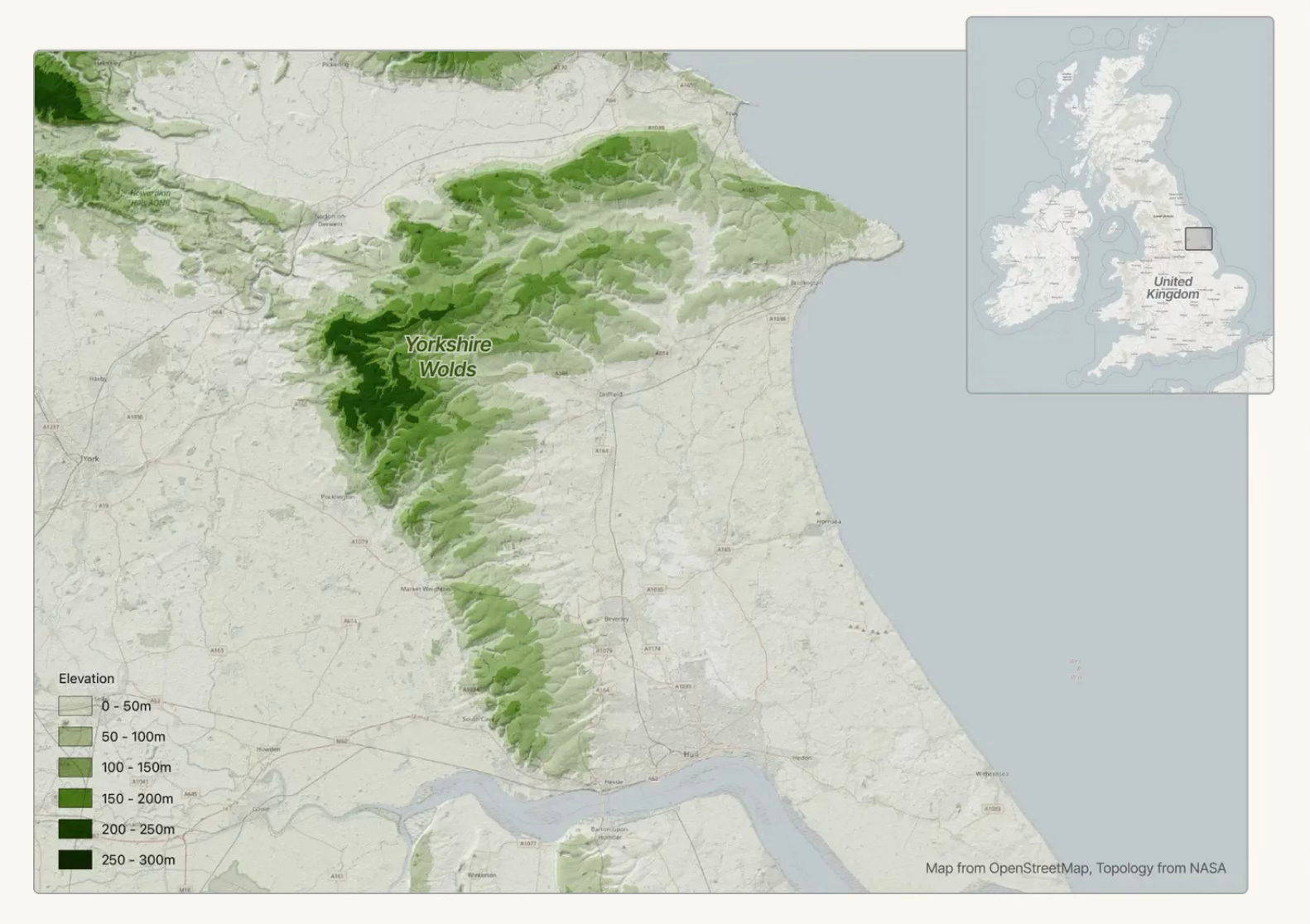

At first glance this countryside of plateaus, dry valleys and low, rolling hills which rise from the mighty Humber estuary at Hessle, then run in a crescent curve, reaching the modest height of 250 metres, finally culminating in the east with the dramatic cliffs of Flamborough Head is a lot more more mild than wild, but frigid winds from the Arctic frequently rake these ancient lands, which are the most northerly outcrop of chalk grassland in Britain. The area is rich in Neolithic, Bronze and Iron Age burial mounds and the ruins of over a hundred deserted mediaeval villages, but eerily empty of people, so there’s a sense of blissful isolation rarely encountered in these overcrowded isles as you traverse its remoteness on the 79 mile Yorkshire Wolds Way. It’s an isolation which is all to the good, as we are here in a brief window between COVID lockdowns.

Sadly this hike is a little too strenuous for my friend David’s two beloved Norfolk terriers Masie and Aggie and his venerable Jack Russell, Monty so we have to get them properly tired out before setting forth on our two day trek.

From the moment we leave the trailhead in horizontal rain and a howling gale, I am glad of my industrial strength waterproofs but immediately regret only protecting my rucksack with a black garbage bag liner, which flaps away noisily in the stiff breeze. Crossing into Nettledale, with over five miles still to go before our lunch stop at The Wolds Inn in the hamlet of Huggate (a pub that a mutual journalist friend had chosen as the York Evening Press’s ‘Inn of the Year’ back in 1991, a long distant recommendation which we hoped might still have a ring of truth to it). Pausing on a hilltop to take in the bleakness of it all we have to lean hard into the wind to avoid being blown over, while a brown hare startled by the racket of my thrashing garbage bag pricks up its ears in the adjacent ploughed field and bolts into the hedgerow.

Arriving soaked to the skin an hour or so later at the Inn, we find the Lounge bar divided up like some open plan office with temporary plastic cubicles to enforce the necessary ‘social distancing’. The Inn’s 1991 prize winning certificate (mysteriously unsigned by our friend the former editor), still hangs in pride of place near the bar. Tucking into our steak and kidney pies and pints, we conclude we should give the place the benefit of the doubt.

The rain is still horizontal when we reluctantly leave an hour or so later, but not for long as trudging with mud clogged hiking boots into Fridaythorpe (yet another evocatively Norse named settlement), which is the highest village in the Wolds, the clouds miraculously part, bathing its lovely 12th century Norman church in sunshine which stays with us all the way through Wormdale and a brace of other glacier-carved valleys to our stop for the night at The Cross Keys in Thixendale, which mirabile dictu, has a drying room for our soaked through gear.

The locals in the bar look like they might be heading for a ‘lock in’ but we are too exhausted to even contemplate joining them.

Climbing up the bank out of the village to Pasturedale after an enormous ‘full English’ breakfast, in cloudy but mercifully dry weather I am struck by a weird feeling which increases all morning long, that I have somehow been teleported back to my early childhood in rural Yorkshire as the landscape and redbrick farmhouses with their old fashioned barns filled with rectangular straw bales, just like the ones we used to play hide and seek in as children, seem so familiar, a feeling reinforced by the uncanny emptiness of the landscape. Sadly, this time travelling bubble does not last as descending the long track to the picturesque ruins of Wharram Percy, we find Britain’s best preserved deserted medieval village rammed with mobile phone toting ramblers. The Norse Wharram (hwerhamm) means "at the bends" and Percy is named after the great northern lords who owned much of this land in the 12th and 13th Centuries. Tragically the Black Death (the mid 14th century bubonic plague pandemic), sheep farming and chronic isolation gradually hollowed out the population, until the last house was finally abandoned in 1500.

Image courtesy of ‘Walking the Wolds’

Beating a hasty retreat from these unexpected crowds we climb past the still inhabited neighbouring village of Wharram-le-Street (Yorkshire is equally full of these eccentrically named post Norman conquest villages, with our favourite being Hutton-le-Hole which means ‘settlement in a hollow’). Ahead of us, framed by trees lies the last valley before journey’s end.

It’s been a modest substitute for the Inca Trail we’d been planning to hike, but seems like a miracle of unexpected freedom, nonetheless.

I get the impression that Marco and his mate David weren't incredibly impressed by the Wolds inn at Huggate. Back in the day, it served the best steak in East Yorkshire and probably in North Yorkshire, too. It was a worthy recipient of the Yorkshire Evening Press's 1991 pub of the year honour. I think I may have the solution to the mystery of the unsigned certificate. Knowing your journalist friend, as I do, I suspect he was unable to write after a heavy, alcohol-laden night out at the award-winning pub.

Thanks for the vicarious wander into the wilds of the Yorkshire Wolds. I would like to visit this area one day. The hike would most likely be beyond my capacity (especially in a driving rain!), but a meal at that inn would be most welcome!